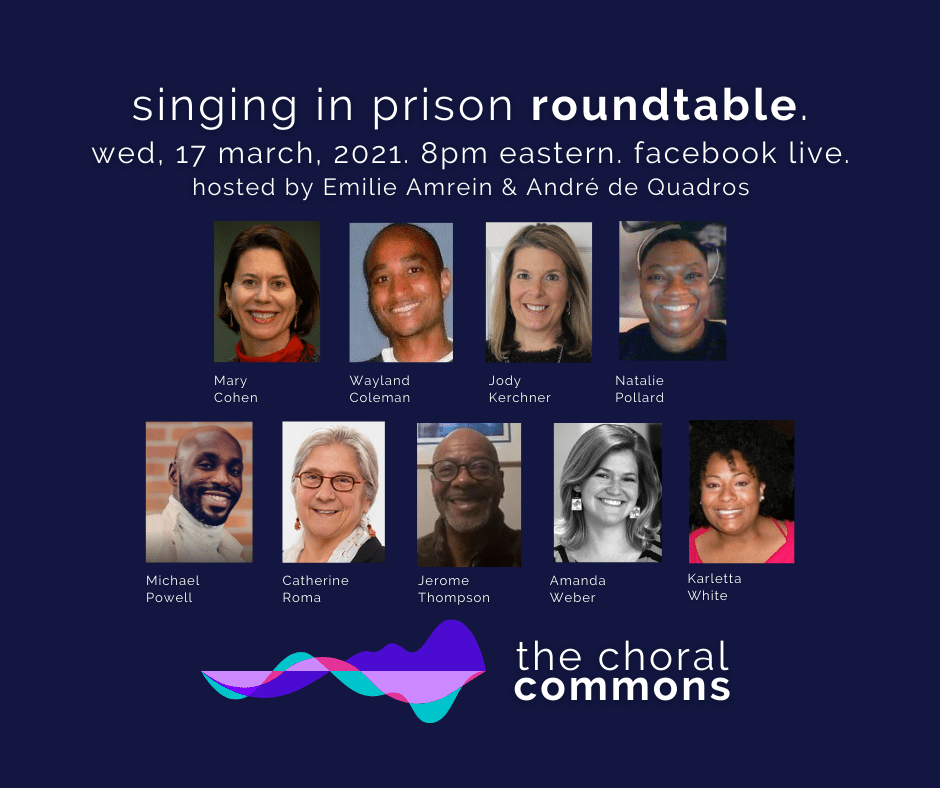

Join us on Wednesday, March 17, 2021, 8:00 p.m., on The Choral Commons Facebook page for a live conversation among prison choral facilitators, restored citizens and community members who participated in “inside” choirs.

Join us on Wednesday, March 17, 2021, 8:00 p.m., on The Choral Commons Facebook page for a live conversation among prison choral facilitators, restored citizens and community members who participated in “inside” choirs.

Dr. Emilie Amrein (University of San Diego) and Dr. Andre DeQuadros (Boston University) hosted an hour-long session with Jody Kerchner (OMAG Choir founder/director) and Jerome Thompson (OMAG Choir founding member & restored citizen) on March 10, 2021 as a part of The Choral Commons Prison Arts series on Facebook.

In this conversation, we discuss how the choir began and issues of “white saviorism,” deprivation of the opposite gender, the impact of prison choir, solitary confinement, freedom practice and liberation even inside of a prison, and building community.

LINK: <https://www.oberlin.edu/conservatory/stage-left>

When Oberlin Professor of Music Education Jody Kerchner started a choir, from scratch, at Grafton Correctional Institution, it was not something she’d had on her bucket list.

Now, five years and many rehearsals later, Kerchner joins former OMAG student choir assistants and Oberlin Strings facilitators for a chat about how their community outreach has not only had a profound impact on their lives but also fostered new understandings for those on both sides of the bars.

“If you can’t envision the sound in your head, you can’t sing it. Just like if you can’t see yourself changing, you won’t. It’s the perspective you hold.”

—Grafton resident/OMAG choir member

It’s Friday afternoon. At this very moment, my choir assistant and I would be in the midst of an OMAG rehearsal. But not for the past two weeks and not for the foreseeable future. Volunteering and visitation have been suspended at the prison until further notice. There’s so much uncertainty in this age of coronavirus. In the midst of crisis or when I need an emotional boost, I’ve always turned to music-making. Certainly, I have the luxury of listening to recordings, watching countless free online archival music performances, and plunking out a few ditties of my own on the piano. But this is eerily solitary. I am keenly aware these days of the meaning that group singing has in my life. Being a choir member is one of the many identities I claim for myself. I “belong” to a choir as a member. As a conductor and singer, I work toward the collective artistic effort that is a common goal of a choir. I participate in a choir because the music stems from a place within myself and contributes to a musical product that is far beyond myself.

And, what about those who are consistently removed from community and are intentionally isolated on a daily basis? How are “my guys” in the OMAG Choir dealing with their new (coronavirus) social-distancing normal, or is this time merely a continuation of their sense of being “removed”? The singers have often said they are removed from prison for 90 minutes weekly, when they are in choir rehearsal. Are they gathering to work on vocal parts in small groups? Are they working on their music theory and sight-reading exercises? Have musical leaders emerged to continue their musical activity, if even in small groups? Is my “insider” accompanist leading mini-rehearsals? What are the OMAG singers doing now, during our regular choir time, even while I write this blog post? Are they as anxious as I am about the pandemic? What resources do they have for their well-being? Is anyone ill?

This time calls for creativity, so what’s my plan? A choir rehearsal cannot “flatten the curve”, but just maybe it gives us all something creative to think about, rather than our overburdened focus on the virus. I’ve been experimenting with a few models for conducting sectional rehearsals, music theory/aural skills training, and small group “voice” lessons using technology. The deputy warden told us today that distance learning is a possibility in some cases. On Monday, I will call the central Ohio Dept. of Rehabilitation & Corrections office and ask for tech support in order to set up distance learning for the OMAG Choir at the Grafton Correctional Institution. Like so many other choir directors’ online posts have stated, I, too, want to remain connected to my choir for the duration of this extreme social distancing. Stay tuned as I explore and report back. I know we can make this happen!

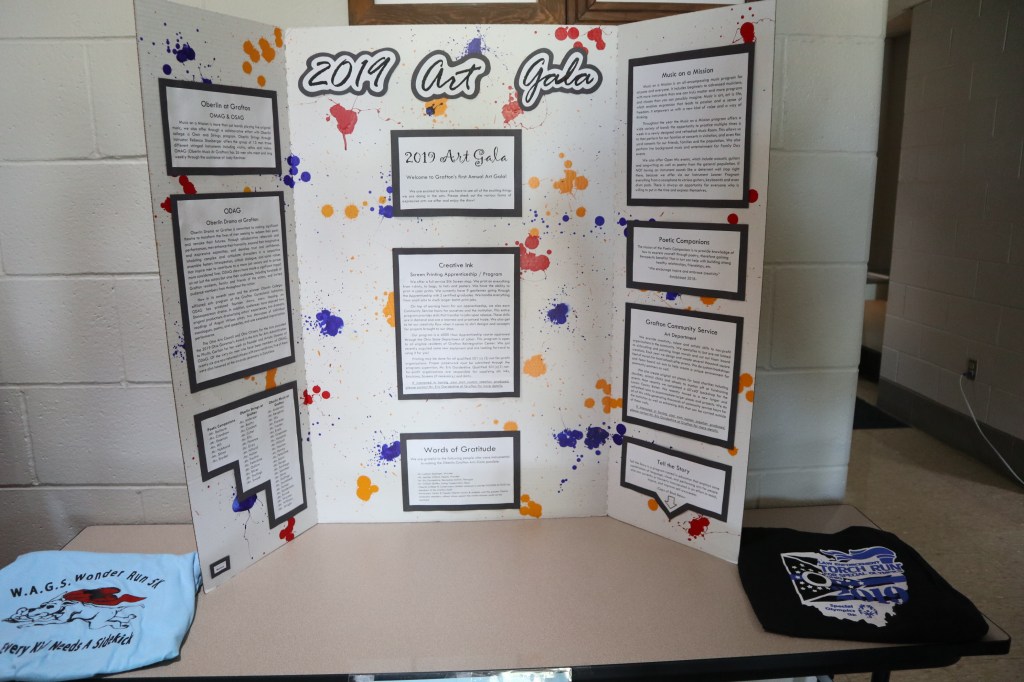

“Beauty before me. Beauty behind me. Beauty above and below and all around.” These are the words of a song that the OMAG Choir singers “signed” and performed during the first GCI Arts Gala.

In preparation of the Arts Gala, I sought volunteers to introduce each song the Choir was to perform. The men wrote out their introductions, some having insightful historical and cultural context, others relaying personal connections to the song. One person in particular offered an introduction that left me speechless and not knowing how to conduct myself, let alone the choir. The resident introduced the song, “Cantar!,” a lively song sung in English and Spanish involving a vocal improvisational section. The men loved singing this piece! Then it happened. The resident spoke “off script.” The resident told the audience that 20 years ago he took someone’s life. He said he regretted this act as a young man (he was 18 years old at the time). Silence. He continued to say that for the first time since his incarceration he felt free as a result of being in the OMAG Choir. Silence. He returned to his place within the choir.

How does one follow this? How does one “break into song” after this introduction? How does one sing a jubilant song? Was I happy? Was I sad? It was my turn. What should I do? My head swirled. Finally, I heard a singer from the back row of the tenor section, commanding, “Come on, Doc, you can do it. Let’s go!” Right, the show must go on. I can unpack later. So onward we went with a renewed musical and emotional intensity. But this is the type of emotional vulnerability the residents, directors, and audience members brought to the arts gala interactions.

To celebrate creative endeavors at the prison, the GCI deputy warden and director of recreational activities collaborated with arts facilitators volunteering within the prison to host the first ever “Arts Gala.” The groups—OMAG Choir, OStrings, Poetry, and Visual Arts— presented a two-day event, the first performance date for the residents’ families/friends and the second for community members from Oberlin, other universities, and prison administration. Following the performance for family members, the residents shared catered boxed meals with their family/friend visitors while being treated by two student performers from the Oberlin Conservatory of Music (a guitarist and a vocalist).

I struggle to find appropriate words to convey the profundity of these two days and the impact they had on me (and from the residents’ commentary, on them too!). The artists were focused and eager to share the fruits of their diligent practice. This event marked the inaugural performance of OStrings and the first OMAG Choir v.2 performance at the GCI. OStrings featured songs from the first Suzuki Book, along with duets and quartets that played music arranged by residents. The OMAG Choir sang a potpourri of songs, including “Lean on Me” in which the audience was asked to sing along. An anteroom was transformed into a visual arts gallery, full of colorful artistic representations and crafts. The Poetry group performed their crafted words. The room was packed each evening with visitors, eager to witness the reason for their invitation to attend. The artists “performed” to an appreciative and engaged audience who clapped along, sang along, moved along, and commented along. The residents’ pride was palpable. Emotions were running high…everyone was joy-full. The artistic offering provided a platform in which prison staff, administration, family, friends, community members, and artists seemed to be interacting with each other on a less hierarchical, interpersonal plane. The families were proud of their son, husband, boyfriend, uncle, brother. The residents were proud of their artistic accomplishments and offerings. I was in awe of the energy and focus the residents brought to their musicianship. The prison administration expressed their pleasure and shared their positive comments with the residents. If even for 90 minutes on two separate evenings, the arts allowed us to freely experience our creative individual and community heart and spirit selves.

One of the joys I’ve experienced as a prison choir facilitator is volunteering alongside of students in my college classes and in choir assistantship capacities. Most semesters since the inception of the OMAG Choir I have selected one or two undergraduate students who serve as OMAG Choir Assistants. These students typically have bass/tenor voices and serve as a vocal model for the OMAG singers. As a person with a treble voice, it is difficult for me to provide a vocal model in the octave in which the bass/treble singers are to sing their vocal parts. For an inexperienced singer, it is quite challenging to hear someone sing a melodic line and then transpose it into their own vocal range. Therefore, having bass/tenor vocal models has been key to working with the OMAG singers. In addition to vocally bolstering a section within the OMAG Choir, student choral assistants conduct sectional (small group) rehearsals, warm-ups, and/or full-group rehearsals of songs that ultimately they conduct in performances at the prison.

Additionally satisfying to observe, however, are the professional relationships that are crafted among the student assistants and the OMAG singers. For the singers, the college students represent the youth that many of the residents did not have or which was truncated for a variety of reasons. Their presence also represents a connection to the “outside” community. The men and assistants share life stories: what the students are studying, what they are practicing for recital presentations, what their professional aspirations are. There are also moments of mentoring. I had a student who was telling the men of coursework that was “less than successful.” The singers gave him a pep talk about the privilege of being in college. The assistants talk about how the experiences with the choir have had a lasting impact on them. Our debriefings in the car rides from the prison back to the college are at times profound.

One of the paradoxical issues about bringing choral assistants and even classes of students (in the course I teach called “Arts Behind Bars”) is that they see the OMAG singers as “ordinary people.” Yes, they could be just like people who the students see walking down the street. Yet within the prison context, there are rules of engagement that must be observed: no exchanging of personal or contact information, no hugs, being aware of one’s physical proximity. The questions arise: “Why do we have to treat the residents differently? They look and act just like we do. Why are the prison rules so limiting, isolating, and demeaning?” So, in one sense, students are experiencing the residents’ humanity demonstrated in their “best possible selves” and yet there are limitations on how they interact with one another. One of my favorite examples of this occurred at the conclusion of an Oberlin-Grafton Arts Gala. I was speaking with a resident and the prison warden. The resident was exhilarated by the OMAG performance (and his solo!). The singer said to me, “Well, I can’t hug you, even though you’re like a mom to me, so I’ll hug the warden instead.” And, he did!

Looks and behaviors…they can be deceiving. We don’t know the triggers and issues that the residents might experience as a result of our interactions with them. The residents don’t know the students’ triggers, either (and there have been some!). We see the men at their best during rehearsals. They love the opportunity to be in the choir and don’t want to lose this “privilege.” We see normalized behaviors and interactions among each other, yet we simply don’t know each other’s story. It is challenging to bring caution into student and resident interactions when each wants to engage in normalcy. And, yet we are volunteering within a prison…

When I reflect on my time facilitating group-singing with the Grafton OMAG v.1 and v.2 Choirs, I find myself grateful that these music-making experiences have become a life “passion point.” You know, those experiences that bring great joy, satisfaction, occasional heartbreak and frustration, and connection to others. I’ve learned so much about myself, my values, my privilege, my shortcomings, and my methods of teaching music. From my observations and singers’ comments, it seems the men have also enjoyed and benefited from our musical engagement throughout the years.

So while I can speak positively about the OMAG experiences and while there are many who eagerly support my volunteer work, my stories are not always met with enthusiasm or an openness to understand. Clearly, the mention of “prison” and my providing the residents with an “artistic experience” (often perceived as “my doing something good” for the residents) provides a trigger for a host of stories, emotions, and stereotypes.

I’ve had people roll their eyes or say words like, “Just let them rot!” I’ve had others recount stories of their lives affected by crime: being mugged and shot or having a brother murdered. These incidents remind me that crime and violence exist in our world, and some of those who inflict it are imprisoned, while others are not (for a variety of sociopolitical reasons). Some of the residents I work with have told me of their remorse for the behaviors that led them to prison. Some have even stated that they are “getting what they deserve.” What they “deserve”? This causes me pause. Imprisonment is so much more complex than punishing people because they “deserve” it. Executing a crime involves personal decision-making and choice, but what situations and circumstances influence one’s choice? Poverty? Mental illness? Addiction? Despair? Desperation? Homelessness? Other? Don’t all people “deserve” love, joy, wholeness, rehabilitation, connection, medical care?

I teach a collegiate course at Oberlin called, “Arts Behind Bars.” It is there that my volunteer arts education work is met with skepticism and sometimes outright opposition. More than once have students (and a few colleagues) called into question my motives as a white, privileged, middle-aged female academic for facilitating a prison choir. I applaud their critical thinking about the subject and understand their arguments about my involvement with the choir, even if I might disagree with some of them. Their biggest objection to my work with the choir, however, is that I am complicit with the structures and values that align with mass incarceration within the United States.

Enter: Existential crisis. Am I supporting the current broken penal system? Truth is I do provide a free educational and recreational service within the penal system; this prison would not otherwise pay for these services. I am providing a service within a system that allows the residents 90 minutes per week of artistic and community “freedom,” yet when the rehearsals conclude this freedom is not sustained for the remaining hours of the day and week. I work diligently at building positive relationships with OMAG singers and prison administration. I value the access the prison administration and staff provide me each week as I run a choir rehearsal. In order to have a rehearsal in the prison, I play by the rules set before me. Given these issues, I am complicit.

This does not mean that I approve of mass incarceration, prolonged incarceration, or the death penalty. This does not mean I am unaware of social ills, including educational pipelines, that lead to prison. This does not mean I am not a prison reformist. I tell my students that I believe in “Loud” and “Quiet” prison activism.

I generally do not consider myself to be a loud person. “Quiet prison activism,” however, is a bit subversive. It works from the inside out. Is this not how a physical wound heals, from the inside out? By building sincere relationships with those I encounter at the prison, I have heard officers’ give positive comments to the men about their music in rehearsals. I have seen wardens and deputy wardens standing, moving, singing along with the residents’ families and the OMAG Choir at an arts gala. By experiencing the choral music with the choir during rehearsals and performances, people witness the residents practicing their “best possible selves” through musical expression. Slowly, gradually, perceptions about the residents and their humanity can change.

Here’s a reality check: Even with prison abolitionist efforts, the prison system as it exists is so inextricably linked to our educational, social, economic, and political systems that it is not going away any time soon. I’m not suggesting abolitionist efforts are ineffective. This “loud activism” is needed! But what about those who are currently imprisoned? Should we not try to educate residents now? Do they not “deserve” to explore their artistry and humanity now? Or should we wait for that moment in time when prisons cease to exist or the penal system radically changes? My approach to quiet activism suggests we move forward how and wherever we can.

It was the Spring of 2018. The OMAG members and I were told that there would be a “de-population” at the minimum-security, reintegration prison in which we rehearsed. What did that mean? The prison administration said that the reintegration center would be undergoing significant construction (primarily roofing), so they needed to place the residents in other prisons. Our prison sponsor also noted that the reintegration center would be for “short-timers” only: a drug treatment rehab center for alleged offenders who would be incarcerated for 45-90 days. What did this all mean for the OMAG Choir, however?

The men recounted stories of residents being moved without warning to another prison location, without being able to notify their family members of their new location. How would I feel if I were unknowingly plucked from my environment and placed in a location in which my family and friends did not know my whereabouts? The men and I had a “goodbye pact”, knowing that at the end of each rehearsal, we did not know who would return to the next rehearsal. We agreed that we would “just know” that we had said our goodbyes and that our hearts traveled with each other. I’ll not forget the day that one of the choir’s “founding fathers” suddenly didn’t show up. This was a fragile person who worked hard to confront his personal issues that had led him to prison. This was a person who was sensitive and didn’t initially know he could sing. This was a person who blushed easily, had “found” religion, and learned to exist within a group of singers. His absence was palpable. And yet we all knew what had happened. It broke my heart.

Person by person in the choir was either released from prison or re-assigned to another prison. Finally, there were four OMAG members who remained in the “choir.” A decision had to be made. This wasn’t really a choir any longer, but I didn’t want to “give up” on the four men who still showed up each Friday afternoon for our 90-minute sing-along. I spoke to the men in mid-December, and we determined we would suspend the OMAG Choir. After three years, was this all there was? A final teary goodbye?

My thoughts darted all over the place on my drive home from the prison. Was I just another person who now abandoned these men? Did I try hard enough to recruit for the choir? A million self-examining questions. Then it occurred to me: I am no longer a prison choir director. My time had been served. I was well satisfied by the many experiences the singers and I had shared and was somewhat willing to entertain the idea that my prison work had ended.

Now it’s January 2019. I received an email from a prison administrator asking me “what I needed…anything” to restart the choir. Ummm…well, choir participants who would consistently show up for rehearsal would be a start! (I stated this response less sarcastically to the email writer!). In an email response, this person then asked if I would be willing to start a choir at the Grafton Correctional Institution, the medium-security prison, just “down the road” from the reintegration center where the OMAG Choir originated. Medium-security…(at this point, you might want to review the first posts of this blog, for the questions I asked then found their way back to me.)

My first “interest session” at the GCI: we met in a large space and there were over 50 men who attended. I remember only one thing—their eyes. For some reason, the residents’ eyes seemed piercing to my very core. What was that about? What was this feeling? Ah, this was a new group. I was doubting if I could be successful starting up another prison choir; was the first choir just a fluke experience? The residents didn’t know the musical joy the original OMAG Choir and I had experienced together. There was no musical history between us. This was ground zero, a potentially new beginning. What were they thinking and feeling? Why did they attend this interest session? What were their musical backgrounds and expectations for the OMAG Choir v.2?

And then I asked a question that I hadn’t planned to ask the residents: “When I leave here today, how many of you will come to the first rehearsal?” Most of the men raised their hands. One person, whom I had met at the reintegration center and who was re-located to the GCI, then asked me: “Will YOU return for a first rehearsal?”

Our first OMAG rehearsal v.2 was the first week of February 2019; 37 men and I attended.

In 2017, I was asked to write a research chapter on group-singing in prison. This chapter would ultimately be included in a multi-volume work entitled, The Routledge Companion to Interdisciplinary Studies in Singing, Vol. 3, “Wellbeing” (Annabel Cohen, Series Editor). I was uncertain whether or not the OMAG singers would wish to participate, and I didn’t want to make “academic” the musical experience we shared. I asked the men their thoughts, and they unanimously (and preliminarily) agreed to participate; they wanted their musical story to be shared. After the WVIZ story on the choir, I knew the singers had to be an integral part of approving the words I would write and the tone of the written presentation.

In this research project, I explored group singing as a catalyst for those incarcerated to develop and practice their musical, personal, emotional, and social competence by developing their intrapersonal and interpersonal skills. Specifically, I questioned (1) how choral singing might be a viable experience for incarcerated people in which to imagine, re-imagine, and practice aspects of their best “possible selves” (Markus & Nurius, 1986), and (2) how participation in prison choir might reflect “freedom practice” (Tuastad & O’Grady, 2013). I collected written survey, interview, and observational data.

How does one begin research approval within a prison? While not a newcomer to the Institutional Review Board (IRB) process for conducting research with human subjects, conducting research within a prison was new to me. After discussing the prospective project with the OMAG singers and gaining written consent, I presented a project proposal to the Grafton deputy wardens for their feedback and ultimate approval. Next was seeking approval from the Oberlin IRB. The full IRB review process required extensive detail and review by a faculty committee that included someone (college or community) who knew the ways of prison life from volunteering, working, or living “on the inside.” In addition, to the Oberlin IRB, I was also required to obtain approval from the Ohio Dept. of Rehabilitation and Corrections IRB. Double duty. Securing approvals from both IRB groups took several months prior to commencing with the research.

While “opinion pieces” and “storytelling” about facilitating arts programs within prisons are common, it is crucial as an arts profession to conduct systematic research with the appropriate approvals in place prior to the beginning of the research. In order to better understand the impact of participating in prison arts programs, facilitators and researchers must bring a critical eye to data in an effort to build the body of research literature. As artists, we assume the benefits of arts education participation, but what do we have to show for it? What do the data say? This is all challenging because the research takes place in a closed society—prison. Prisoners are considered by the Belmont Report (45 CFR 46 Subpart C) a vulnerable population, because their ability to make an informed and voluntary decision to participate in research is compromised; they have diminished autonomy. The category of “permissible prison research” that my study addressed was “research on practices, both innovative and accepted, which have the intent and reasonable probability of improving the health or well-being of the subject.” The IRB approvals help to insure that the research is grounded in professional ethics, such that the prisoners’ autonomy, beneficence, and justice is being maintained. While the singers might not have the opportunity to exercise much personal choice in prison, their freedom to choose to participate in as much of the research process as they wanted was guaranteed in this research project.

The published chapter is due out in early 2020! Stay tuned.