When I reflect on my time facilitating group-singing with the Grafton OMAG v.1 and v.2 Choirs, I find myself grateful that these music-making experiences have become a life “passion point.” You know, those experiences that bring great joy, satisfaction, occasional heartbreak and frustration, and connection to others. I’ve learned so much about myself, my values, my privilege, my shortcomings, and my methods of teaching music. From my observations and singers’ comments, it seems the men have also enjoyed and benefited from our musical engagement throughout the years.

So while I can speak positively about the OMAG experiences and while there are many who eagerly support my volunteer work, my stories are not always met with enthusiasm or an openness to understand. Clearly, the mention of “prison” and my providing the residents with an “artistic experience” (often perceived as “my doing something good” for the residents) provides a trigger for a host of stories, emotions, and stereotypes.

I’ve had people roll their eyes or say words like, “Just let them rot!” I’ve had others recount stories of their lives affected by crime: being mugged and shot or having a brother murdered. These incidents remind me that crime and violence exist in our world, and some of those who inflict it are imprisoned, while others are not (for a variety of sociopolitical reasons). Some of the residents I work with have told me of their remorse for the behaviors that led them to prison. Some have even stated that they are “getting what they deserve.” What they “deserve”? This causes me pause. Imprisonment is so much more complex than punishing people because they “deserve” it. Executing a crime involves personal decision-making and choice, but what situations and circumstances influence one’s choice? Poverty? Mental illness? Addiction? Despair? Desperation? Homelessness? Other? Don’t all people “deserve” love, joy, wholeness, rehabilitation, connection, medical care?

I teach a collegiate course at Oberlin called, “Arts Behind Bars.” It is there that my volunteer arts education work is met with skepticism and sometimes outright opposition. More than once have students (and a few colleagues) called into question my motives as a white, privileged, middle-aged female academic for facilitating a prison choir. I applaud their critical thinking about the subject and understand their arguments about my involvement with the choir, even if I might disagree with some of them. Their biggest objection to my work with the choir, however, is that I am complicit with the structures and values that align with mass incarceration within the United States.

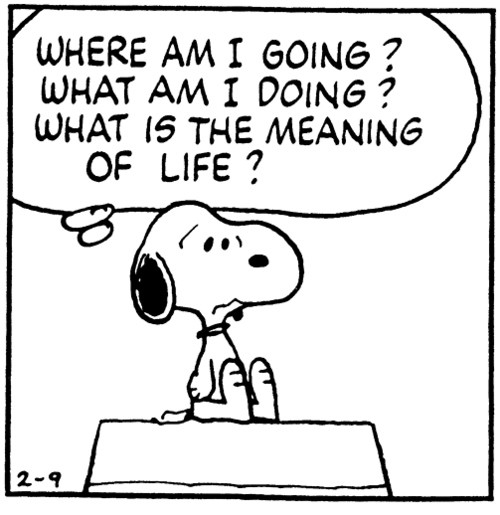

Enter: Existential crisis. Am I supporting the current broken penal system? Truth is I do provide a free educational and recreational service within the penal system; this prison would not otherwise pay for these services. I am providing a service within a system that allows the residents 90 minutes per week of artistic and community “freedom,” yet when the rehearsals conclude this freedom is not sustained for the remaining hours of the day and week. I work diligently at building positive relationships with OMAG singers and prison administration. I value the access the prison administration and staff provide me each week as I run a choir rehearsal. In order to have a rehearsal in the prison, I play by the rules set before me. Given these issues, I am complicit.

This does not mean that I approve of mass incarceration, prolonged incarceration, or the death penalty. This does not mean I am unaware of social ills, including educational pipelines, that lead to prison. This does not mean I am not a prison reformist. I tell my students that I believe in “Loud” and “Quiet” prison activism.

I generally do not consider myself to be a loud person. “Quiet prison activism,” however, is a bit subversive. It works from the inside out. Is this not how a physical wound heals, from the inside out? By building sincere relationships with those I encounter at the prison, I have heard officers’ give positive comments to the men about their music in rehearsals. I have seen wardens and deputy wardens standing, moving, singing along with the residents’ families and the OMAG Choir at an arts gala. By experiencing the choral music with the choir during rehearsals and performances, people witness the residents practicing their “best possible selves” through musical expression. Slowly, gradually, perceptions about the residents and their humanity can change.

Here’s a reality check: Even with prison abolitionist efforts, the prison system as it exists is so inextricably linked to our educational, social, economic, and political systems that it is not going away any time soon. I’m not suggesting abolitionist efforts are ineffective. This “loud activism” is needed! But what about those who are currently imprisoned? Should we not try to educate residents now? Do they not “deserve” to explore their artistry and humanity now? Or should we wait for that moment in time when prisons cease to exist or the penal system radically changes? My approach to quiet activism suggests we move forward how and wherever we can.

Jody–This rings so true for me. I face the exact same circumstances with my programming work inside. Thanks for your forthright thoughts on these issues, and for giving voice to the complexities of offering programming behind bars.

LikeLike